Democracy Dies in Deceptive Data

Op-ed “correction” only serves to further undermine Benjamin Park and the Washington Post’s credibility.

The Washington Post issued the following correction for Benjamin Park’s op-ed from August 24, 2021, entitled “Even LDS leaders are struggling to get Mormons vaccinated against the coronavirus.”

While the vaccination rates cited are now technically true, the correction did nothing to repair the misperceptions perpetuated by the piece’s initial bad data. In fact, the “correction” is worse than the initial error. In the original piece, anyone could have clicked on the link provided and seen that Park had goofed his numbers, but now, after the deletion of the word “eligible” in citing Utah vaccination rates, it takes some background knowledge of Utah’s demographic profile to understand that the statistics Park is relying on to make his point are totally useless.

Park and the Washington Post were given a chance to use much more accurate and useful statistics—i.e., the correct eligible vaccination rates of Utah in comparison with other states across the country—but they chose to use the nearly meaningless metric of total vaccination rates as their correction. As I alluded to in my last piece, while it may have been technically true that Utah fell in the lower half of the country in “total vaccination rates,” this metric didn’t take into account Utah’s significantly younger demographics, which effectively makes total vaccination rate a meaningless statistic.

It’s okay to make mistakes. But when someone points out your mistake and you choose inferior and deceptive metrics—metrics that conveniently bolster your overall thesis—then you’re in a worse place than where you started. The choice to rely on total vaccination rates instead of eligible vaccination rates undermines The Washington Post and Park’s credibility. It’s a convenient metric for Park’s argument, but it’s a dishonest one, and it solidifies the impression that Park’s piece relies heavily on cherry-picked evidence and deceitful framing that ignores contradictory and complicating evidence that would undermine his narrative.

This approach is shameful and carries negative repercussions, but before we get there, I want to make it absolutely clear why it’s a problem that Park chose to go with total vaccination rates as opposed to eligible vaccination rates for his “correction.” To explore why this choice is so egregious, let’s take a detour to two imaginary towns, Appleton and Orangeville.

A Tale of Two Towns

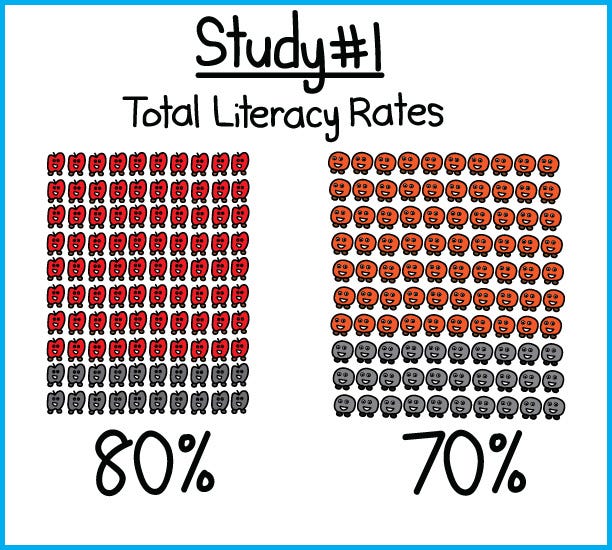

Appleton and Orangeville are two little towns, each with a population of 100 inhabitants. A social scientist decides to study literacy rates in both towns and finds that the total literacy rate for Appleton is 80 percent, while in Orangeville, it is 70 percent. The social scientist concludes that Appleton values literacy more than Orangeville.

This conclusion sounds plausible until you find out that the social scientist failed to account for a critical factor: the number of children under the age of five. It turns out that 10 percent of Appleton’s population is under the age of five, but 25 percent of Orangeville’s population is under five.

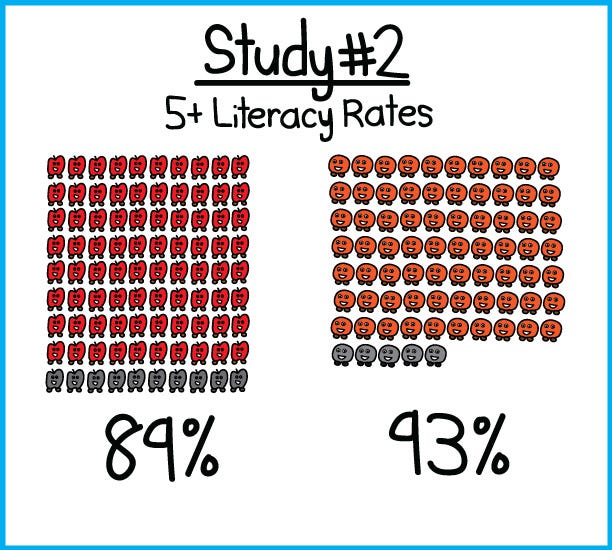

A subsequent researcher decides to revisit the two towns, but in her study, she takes age into account. She compares the literacy rates only for residents over the age of five. In her study, she finds that 80 out of 90 Appleton residents over five can read—a literacy rate of 89 percent—while 70 out of 75 Orangeville residents over five can read—a literacy rate of 93 percent. She concludes that Orangeville actually has the higher literacy rate, exactly the opposite conclusion of the first researcher.

So which researcher has the more accurate conclusion? After all, the math for both studies is correct. But the analysis for the first study is flawed: it really doesn’t make sense to include young children who haven’t had much of a chance to learn to read yet when comparing literacy rates for the two towns. If you don’t control for that variable, you get a muddled picture that doesn’t accurately reflect reality on the ground. It’s the second study that is useful for measuring literacy rates.

Park’s Use of Total Vaccination Rates

Park ran into the problem of the first researcher. He used total vaccination rates to compare Utah to the rest of the country, but the total vaccination rates didn’t exclude all the kids under twelve who couldn’t even be vaccinated yet. Only when those children were excluded from the data could any sort of meaningful analysis be made, especially given the higher proportion of children to adults in Utah’s population in comparison with other states. That’s why it was essential to use eligible vaccination rates to compare across states. Otherwise, you ended up with useless, or even harmful, conclusions.

As I outlined in my previous post, I consulted the Mayo Clinic’s vaccine tracker (from August 18th, a week before Park’s op-ed ran) to compare fully vaccinated rates of eligible residents in each state for the three demographic categories provided: under 18, 18-64, and 65+. In the under-18 fully vaccinated rates, Utah was at 14.2% vaccinated, tied for 25th place. For the 18-64 demographic, Utah’s fully vaxxed percentage came in at 62.3%, at 17th place. And for the 65+ demographic, Utah was at 90.4%, at 20th place.

Any serious scholar presented with these statistics would pause and realize that the reality on the ground is more complicated than they had initially perceived. That Park was informed of these better metrics and chose to go with the total vaccination rates is deeply disappointing.

Let’s be clear that no one is denying that there are plenty of Covid-19 vaccine skeptics in the Church. That was never at issue. The initial problems with Park’s piece were that he went with data that confirmed both his priors and his reductive qualitative analysis and that he and the Washington Post misread very simple charts, providing yet another example of the incompetency of our expert class.

These mistakes were bad enough, but the choice to use total instead of eligible vaccination rates has only made them worse. It certainly would have been hard for Park to rework his piece to take into consideration the better data. In fact, if he cited meaningful metrics, his op-ed would lose much of its force.

Additionally, a more nuanced look at the data calls into question Park’s historical analysis. Just to reiterate, on August 18th, the vaccination rate of Utahns over the age of 65 was 90.4 percent, placing it 20th in the country. The conservative forces Park points to as determinative for members’ distrust and skepticism would have been most formative for the collective consciousness of this 65+ demographic, and yet a significant majority of Utah seniors were outperforming many other states.1 If anyone should be affected by the conservative influences Park points to, it should be these oldest members, but I know plenty of Fox News-watching Republican members over 65 who have been vaccinated. No wonder Park chose to paint over his mistake instead of admitting that his analysis was flawed.

The Damage Done

As the reporter Glenn Greenwald rightly observes, “it is virtually a religious belief in the dominant liberal culture that people who do not want the COVID vaccine are stupid, ignorant, immoral and dangerous.” When Park dishonestly frames Utah’s vaccination rates as lower than they really are, he is playing off these negative stereotypes to drive home his narrative of the anti-intellectualism he sees in recent Church history, even if the data says otherwise.

Why spend the time to point this out? Just read the comment section below Park’s op-ed. It’s littered with ugly stereotypes about members of the Church. Park’s portrayal of his fellow brothers and sisters is feeding bigotry and prejudice among the wider public, and he should know better, especially as a professor who studies Church history. He almost certainly has read the slanderous lies printed in newspapers of the past about members of the Church and the harm those words have done in the real world. It should be horrifying to know that his careless words are contributing to that same hateful spirit.

Park can’t undo the damage he has done: he can’t track down everyone who read his op-ed. But he can set the record straight, if only for scholarly and journalistic integrity. What remains to be seen is whether Park will step up to the challenge.

After writing this piece, I found that Jeff Lindsay made a similar point in response to our initial Substack piece. You can read more here: https://latterdaysaintmag.com/zeal-without-data-blaming-the-church-for-utahs-allegedly-low-vaccination-rates/